津田修吾

津田修吾Have you ever felt that Japanese flower arrangements have a calm, almost spiritual vibe but couldn’t explain why?

If so, you’re not alone. Kado, Japan’s 「Way of Flowers,」 is full of meaning that isn’t obvious at first glance.

In this guide, we’ll break it down simply

What Kado really is, how it differs from ikebana and Western floral art, and where you can try an English-friendly lesson in Tokyo or Kyoto.

Curious why Japanese floral art feels so special?

You’ll understand it clearly—and know exactly where to experience it yourself.

Why Flowers Hold a Special Place in Japanese Culture

Flowers have played a central role in Japanese culture for centuries. They carry symbolic meaning and serve as a bridge between nature and human expression. In Japan, nature is deeply woven into daily life, and this cultural mindset helped shape Kado — Japan’s “Way of Flowers.”

Seasonality and the Aesthetic of Impermanence

Japan’s four distinct seasons foster a cultural sensitivity to impermanence, reflected in the idea of wabi-sabi.

Seasonal awareness is essential in Kado, where choosing flowers expresses time, atmosphere, and emotion.

- Flowers express the present moment of nature.

- Arrangements shift depending on climate, festivals, and cultural events.

- Seasonal transitions communicate subtle emotions without words.

| Season | Typical Flowers | Symbolic Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Spring | Cherry blossoms, plum | New beginnings, hope |

| Summer | Iris, hydrangea | Vitality, rainfall, resilience |

| Autumn | Chrysanthemum, autumn grasses | Maturity, reflection |

| Winter | Pine, camellia | Strength, endurance |

Nature, Symbolism, and Japanese Arts

Japanese traditional arts emphasize observing and harmonizing with nature. Kado expresses harmony through balance, symbolic storytelling, and meaningful space.

Rather than focusing on volume or symmetry, practitioners highlight asymmetry, emptiness, and the natural character of each element.

- A single upright branch can symbolize aspiration or spiritual growth.

- Empty space represents harmony, balance, and potential.

- Natural curves and imperfections reflect authenticity over perfection.

What Is Kado: Japan’s “Way of Flowers”

Kado, often translated as the Way of Flowers, is a refined Japanese art form that goes far beyond arranging plants in a vase.

It is a cultural practice rooted in mindfulness, using flowers to express the beauty of life, nature, and time. Rather than focusing on decoration, Kado emphasizes intention, awareness, and a deep respect for natural form.

This is why many travelers describe Kado not as simple “flower arranging,” but as an encounter with the Japanese spirit of harmony.

Kado as a Mindful Art of Harmony and Discipline

Kado encourages practitioners to observe plants as living beings with their own shape, direction, and silent emotion. Through slow movements and thoughtful placement, one cultivates presence—similar to meditation.

The goal is harmony: harmony between the arranger and the material, harmony among the materials, and harmony with the surrounding space.

- Calming ritual that slows the mind

- Disciplined practice similar to tea ceremony or calligraphy

- Way to reconnect with seasonal beauty

This blend of mindfulness and structure is what gives Kado its timeless appeal.

Core Principles: Line, Space, and Balance

In Kado, every element has purpose and meaning.

The composition follows three essential principles that guide both the structure and the spirit of the arrangement.

| Principle | Meaning | Role in Kado |

|---|---|---|

| Line (Sen) | The direction and flow created by branches | Brings movement and expresses life force |

| Space (Ma) | The intentional empty space around materials | Creates depth, silence, and a sense of breath |

| Balance ( Chōwa) | Harmony among materials, shape, and container | Reflects the equilibrium found in nature |

Line gives character, space gives dignity, and balance gives unity.

These principles are applied through sensitive observation rather than strict rules, allowing even simple branches to express elegance and emotion.

Kado, Ikebana, and Western Floral Art: Key Differences

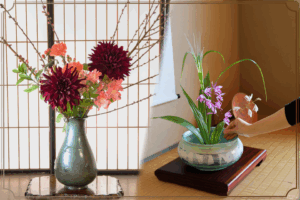

Kado and Ikebana differ from Western floral art in intention, philosophy, and use of space.

While Western arrangements focus on visual fullness and color harmony, Kado emphasizes spiritual discipline, symbolic meaning, and the relationship between nature, space, and the arranger.

Understanding these contrasts helps visitors see why Kado is considered one of Japan’s refined traditional arts.

Purpose and Aesthetic Philosophy

Kado views flowers as living materials that express seasonality, time, and the arranger’s inner emotion.

This mindset connects deeply with Japanese aesthetics such as wabi-sabi, which values imperfection and transience.

By contrast, Western floral design typically aims for

- Visual abundance

- Color balance and symmetry

- Immediate decorative impact

Ikebana, which evolved from Kado, shares its spiritual roots but tends to allow broader creative freedom in modern practice.

In Kado, the purpose remains harmony between line, space, and natural form, creating a reflective and calming beauty.

Materials, Tools, and Techniques

Because Kado and Western floral art approach arrangement differently, their tools and materials also diverge.

The table below highlights the essential contrasts.

| Aspect | Kado / Ikebana | Western Floral Art |

|---|---|---|

| Materials | Seasonal branches, buds, natural curves, uneven stems | Fully-bloomed flowers, uniform stems |

| Tools | Kenzan (needle holder), shallow vase (suiban), Japanese shears | Floral foam, tall vases, wired stems |

| Focus of Technique | Use of empty space, asymmetry, natural line expression | Creation of volume, round shapes, color density |

| Symbolism | Strong—arrangements reflect seasons, life, balance | Limited—primarily decorative |

In Kado, the arranger often trims branches to reveal their natural “line,” positioning them intentionally.

Techniques emphasize height, angle, negative space, and emotional expression.

Meanwhile, Western floral art focuses on forming a cohesive bouquet in which flowers blend visually as a unified whole.

A Brief History of Kado

Kado, often described as the Way of Flowers, has evolved for nearly a thousand years.

Its history reflects Japan’s spiritual values, aesthetic sensibilities, and the transition from temple rituals to refined artistic practice.

Understanding this journey explains why Kado remains one of Japan’s most respected traditional art forms.

From Buddhist Offerings to Court Culture

The earliest roots of Kado reach back to the 6th century, when flowers were placed at Buddhist temples as offerings to honor the spirits. These early arrangements were simple and symbolic, emphasizing purity and devotion.

By the Heian and Muromachi periods, flower offerings moved from temples to aristocratic residences. The practice shifted from religious ritual to a refined courtly art expressing harmony, balance, and seasonal awareness. During this time, people began recognizing that flowers could reflect human emotion and the natural order.

The Birth of Schools: Ikenobo and Beyond

The formalization of Kado began in the 15th century with the establishment of the Ikenobo school. Based at Kyoto’s Rokkaku-do Temple, Ikenobo masters developed structured styles such as rikka, emphasizing vertical lines, spiritual symbolism, and natural landscapes.

From this foundation, new schools emerged. Some preserved classical forms, while others responded to social change with more expressive and flexible arrangements. This diversity allowed Kado to spread from monks and aristocrats to samurai, townspeople, and eventually the wider public.

| Era | Main Characteristics | Cultural Influence |

|---|---|---|

| 15th–16th century | Ikenobo establishes formal rules | Spiritual symbolism, temple culture |

| Edo period | Diverse schools flourish | Samurai aesthetics, tea culture |

| Modern era | Freer, expressive styles | Individual creativity, global interest |

Modern Evolution and Contemporary Styles

In the 20th century, Japan’s modernization sparked a wave of innovation. Schools such as Sogetsu introduced avant-garde styles that embraced unconventional materials, sculptural forms, and personal expression.

This movement elevated Kado from a traditional cultural art to a form recognized within modern art circles.

Today, Kado spans a wide spectrum—from classical, highly structured arrangements to contemporary works exhibited around the world.

What remains constant is the deep respect for nature, seasonality, and the mindful act of arranging with intention.

- Integration of natural and man-made materials

- Artistic expression that reflects the arranger’s personality

- Global workshops and exhibitions attracting international students

Kado continues to evolve while preserving its philosophical roots, making it a living tradition that resonates with both Japanese practitioners and global audiences.

The Three Major Schools of Kado

Japan’s art of flower arrangement—known as Kado or ikebana—has developed through several influential schools. Ikenobo, Ohara, and Sogetsu are recognized as the three most significant traditions, each offering its own history, aesthetic values, and teaching philosophy.

These schools provide visitors with unique ways to experience authentic Japanese flower arrangement during their trip to Japan.

| School | Origin & Historical Background | Artistic Style | Recommended For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ikenobo | Began in 15th-century Kyoto at Rokkaku-do Temple | Formal, symbolic, highly structured | Visitors seeking the most traditional form of Kado |

| Ohara | Founded in the late 19th century during Western cultural influence | Nature-inspired, landscape-like, known for Moribana | Beginners and those who enjoy natural, garden-like designs |

| Sogetsu | Established in 1927 as a modern creative movement | Freeform, sculptural, contemporary | Travelers interested in modern Japanese arts and creative expression |

Ikenobo: The Origin of Kado

Ikenobo is the oldest and most foundational school of Kado, originating from Buddhist monks at Kyoto’s Rokkaku-do Temple who offered flowers in devotion.

Over centuries, this ritual developed into a refined artistic discipline.

- Balance of heaven, earth, and humanity (shushi), forming the core structure of its arrangements.

- Symbolic expression, where each stem carries meaning.

- Formal beauty emphasizing dignity, precision, and seasonal awareness.

For travelers seeking the most historically authentic form of Kado in Japan, Ikenobo represents the classical heart of the art.

Ohara School: Blending Tradition and Western Influence

The Ohara School emerged during Japan’s early modern era, when Western flowers, colors, and aesthetic ideas began influencing Japanese life.

Rather than staying bound to temple traditions, Ohara embraced these new elements and created more accessible, visually expressive forms of Kado.

- Incorporation of Western flowers such as dahlias and roses.

- Creation of Moribana, a shallow-bowl arrangement designed to resemble natural scenery.

- Focus on color layering and spatial depth, drawing from Japanese gardens and Western landscapes.

Because of its gentle, natural appearance, Ohara is ideal for beginners or visitors exploring ikebana classes in Tokyo or Kyoto.

Sogetsu School: Modern and Creative Expression

The Sogetsu School, founded by Sofu Teshigahara in 1927, revolutionized Kado with its modern creative philosophy.

Its guiding belief—“Ikebana can be created anytime, anywhere, with any materials”—opened the art form to bold experimentation.

- Freedom of materials, including metal, driftwood, glass, or recycled objects.

- Sculptural forms often displayed in museums and contemporary art settings.

- Universal appeal, making it one of the most internationally appreciated schools.

For travelers who love modern design or contemporary Japanese culture, Sogetsu provides a fresh, artistic, and expressive approach to Kado.

Kado in the World Today

Today, Kado has evolved from a traditional Japanese art into a global cultural practice embraced by people seeking mindfulness, aesthetic refinement, and a deeper connection with nature.

While its roots remain in Japan, Kado is now practiced and appreciated worldwide in museums, universities, luxury hotels, and cultural centers. Some discover it while traveling in Japan, while others encounter it through international exhibitions, online lessons, or Ikebana associations. This global presence reflects Kado’s universal appeal and timeless philosophy.

Global Expansion and Cultural Influence

Kado spread globally as major schools began overseas exhibitions and established international chapters.

Its rise coincided with growing worldwide interest in mindfulness, minimalism, and Japanese aesthetics. As a result, Kado is now woven into education, cultural diplomacy, and even corporate wellness programs.

- International Exhibitions: Sogetsu, Ohara, and Ikenobo artists display works in New York, Paris, London, and Singapore.

- Educational Programs: Universities and art institutes include Ikebana courses within Japanese studies or fine arts.

- Cultural Diplomacy: Japanese embassies and cultural centers use Kado demonstrations to share harmony and respect.

- Corporate Workshops: Companies adopt Kado to encourage mindfulness, creativity, and team cohesion.

Global Cultural Influence at a Glance

| Region | Influence of Kado | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|

| North America | Appreciation for mindfulness and modern minimalism | Sogetsu exhibitions, university Ikebana clubs |

| Europe | Integration into contemporary design and sustainability trends | Paris art fairs, London Zen garden events |

| Southeast Asia | Cultural exchange and hospitality industry adoption | Luxury hotel experiences in Singapore & Bangkok |

Kado’s international growth reflects a global desire to reconnect with nature, mindfulness, and inner calm.

Why Kado Appeals to International Audiences

For many visitors, Kado offers more than a floral art lesson it opens a window into the Japanese worldview, where balance, attention, and sensitivity shape everyday life.

- A mindful creative experience: Kado emphasizes stillness, intention, and the relationship between humans and nature, aligning with global wellness trends.

- Aesthetic simplicity with deep meaning: Many are drawn to wabi-sabi — beauty in impermanence and natural imperfection.

- Accessibility for beginners: Even first-time learners can create expressive works by focusing on line, space, and natural form.

- A cultural gateway to Japan: Practicing Kado connects travelers with Japanese values such as harmony, respect, and the idea of “dō” — a path of mindful living.

- Universal visual language: Flowers transcend language, allowing Kado to be practiced and appreciated anywhere in the world.

What Makes Kado Especially Attractive to Travelers

- A memorable hands-on cultural activity

- A peaceful moment during a busy travel schedule

- A meaningful souvenir — photos of their own arrangement

- A direct encounter with Japanese tradition beyond sightseeing

In a fast-paced, overstimulated world, Kado offers a rare experience: creating something beautiful while becoming quietly present.

FAQ About Kado and Ikebana

Kado often raises questions among visitors who are discovering Japanese flower arts for the first time. Below are clear explanations to help international travelers understand this cultural tradition before experiencing it in Tokyo or Kyoto.

- Is Kado the same as Ikebana?

-

Kado and Ikebana are related but not identical.

Kado refers to the “Way of Flowers,” a cultural path centered on harmony, discipline, and personal cultivation similar to other Japanese dō arts such as tea ceremony and calligraphy. Ikebana is the artistic practice that grew within this tradition.

Kado represents the philosophy and spiritual foundation, while Ikebana focuses on the technique and act of arranging flowers. Both share the same roots, but Kado expresses the broader mindset behind the practice.

- Can beginners try Kado during their trip to Japan?

-

Yes,Kado is very beginner-friendly, and many studios in Tokyo and Kyoto welcome first-time learners.

Travelers can enjoy a calm, meditative experience as instructors guide them through the use of seasonal materials and the essential elements of line, space, and balance.

No prior experience is required, and sessions are often designed for international guests who want to explore traditional culture through hands-on learning.

- What makes Kado different from Western flower arrangements?

-

Kado differs most clearly in its intention and aesthetic philosophy.

While Western floral design often focuses on volume, color richness, and decorative impact, Kado values simplicity, asymmetry, and expressive empty space. Each flower or branch is treated individually, reflecting nature and the arranger’s state of mind.

This philosophical depth shaped by Zen and the Japanese appreciation of impermanence gives Kado a quiet emotional resonance that sets it apart from Western arrangements.

Experience Kado in Japan: Where to Learn and Practice

Experiencing Kado in Japan is the most authentic way to understand its harmony, discipline, and cultural depth. Tokyo and Kyoto offer ideal environments for hands-on lessons, where traditional schools and modern studios welcome beginners with English-speaking instructors.

Many workshops introduce essential concepts such as balance, line, and the quiet appreciation of wabi-sabi—the beauty of impermanence and simplicity. Most lessons provide all materials, allowing first-time learners to create their own arrangement with confidence.

For travelers seeking a meaningful cultural experience, Kado lessons offer a memorable and intimate window into Japanese artistry.

・元プロボクサー 柔道有段者 アームレスリング選手

・元飲食店5店舗の代表取締役であり、飲食業界の総合コンサルタント、広告クリエイター

・独自の視点と挑戦を続ける姿勢で、SEOやWebマーケティングに関する記事を執筆しLPのコンバージョン率UP

・海外でのビジネス経験を持ち、国際的な視点からもアプローチ

・現在、山奥で狩猟生活|Web戦略・SEO・LP制作・チャットボット構築支援を行う

・生成AI×プロ編集でSEO記事制作を推進。勝てるキーワードから集客導線を設計。

・構成設計からHTML入稿、効果測定まで伴走。