Curious about Japanese customs?

From bowing and taking off shoes to saying Itadakimasu, Japan’s daily life is filled with unique traditions that reflect respect and harmony.

Discover 15 essential Japanese customs and manners—each explained clearly in English with cultural context and real-life examples.

Perfect for English learners, tour guides, and travelers, this guide helps you understand and confidently explain Japan’s everyday etiquette to the world.

Everyday Japanese Customs and Traditions

Many Japanese customs shape everyday life — from eating and greeting to showing respect.

These traditions reflect Japan’s core values of harmony, cleanliness, and consideration for others.

From dining and bathing to gift-giving, here are some common customs that will help you fit in naturally and fully enjoy Japan’s beautiful culture.

Taking Off Shoes Indoors

In Japan, people remove their shoes before entering homes to keep the space clean and show respect.

Most houses, temples, and ryokan (traditional inns) have a genkan (entrance area) where shoes are taken off before stepping inside.

This custom reflects the idea of separating “outside” from “inside”. Shoes are placed neatly by the door, and slippers are often provided — so wearing clean socks is always a good idea.

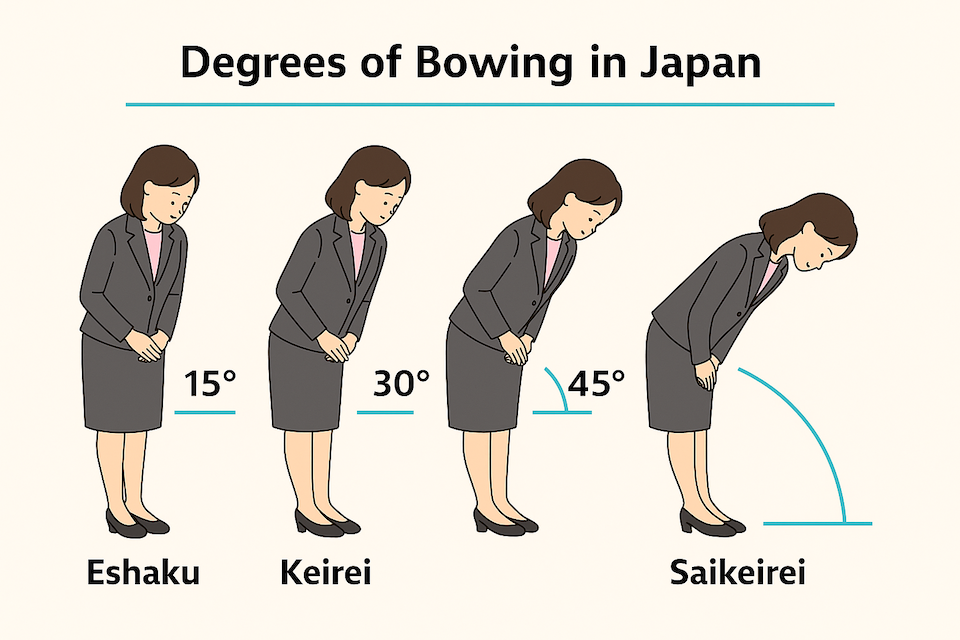

Bowing to Greet

A bow (お辞儀, ojigi) can range from a light nod (eshaku, 会釈) to a 30° polite bow (keirei, 敬礼) or a deep 45° bow (saikeirei, 最敬礼) used for deep respect or apology.

Visitors don’t need to bow perfectly — just a small nod or gentle bend with a smile is enough.

Bowing reflects Japan’s values of respect and humility—simple gestures that speak volumes.

Saying “Itadakimasu” Before Meals

Before eating, Japanese people say “Itadakimasu”, meaning “I humbly receive”.

This simple phrase shows gratitude to everyone and everything that made the meal possible. It’s not religious, but a daily expression of respect and appreciation.

After finishing, they say “Gochisōsama-deshita”, meaning “Thank you for the meal”.

Together, these phrases reflect Japan’s deep sense of gratitude—acknowledging that every meal is a shared effort and a gift to be appreciated.

Bathing Culture and Onsen Rules

Japanese people bathe daily, often soaking in deep tubs at home or in communal hot springs.

Bathing is as much about relaxation as cleanliness — first wash and rinse, then soak quietly in clean water.

At onsen (hot springs) and sento (public baths), follow local etiquette: no swimsuits, keep towels out of the water, and respect others’ space.

This soothing ritual reflects Japan’s love of purity, health, and harmony—a moment of calm for both body and mind.

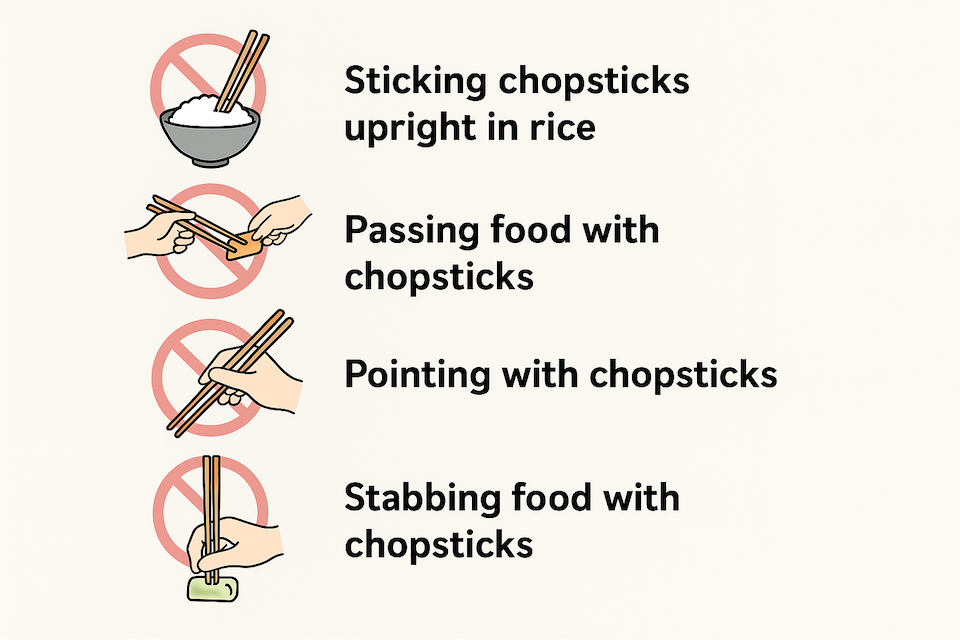

Proper Use of Chopsticks

Chopsticks (お箸, ohashi) are Japan’s main eating utensils, and using them properly shows good manners.

Never stick chopsticks upright in rice or pass food from one pair to another—both resemble funeral customs. Instead, use the clean end of your chopsticks to share food.

Avoid waving, pointing, or stabbing food, and place them neatly on a rest when not in use.

These small gestures reflect Japan’s respect and mindfulness at the table—even a little effort is always appreciated.

Drinking Unsweetened Tea

Tea in Japan is usually enjoyed plain—without sugar or milk. The most common types are green tea (緑茶, ryokucha), barley tea (麦茶, mugicha), and roasted green tea (ほうじ茶, hojicha).

You’ll often be served unsweetened hot tea at restaurants or cold barley tea in summer. Even matcha (抹茶) during tea ceremonies is served plain.

When offered tea, don’t ask for sugar—just enjoy its natural flavor.This simple custom reflects Japan’s love for purity and balance in everyday life.

Using Wet Towels (Oshibori)

In Japan, restaurants offer a wet towel (おしぼり, oshibori) before meals — a small gesture of omotenashi (hospitality).

Use it only to clean your hands, then place it neatly aside.

This simple custom reflects Japan’s respect for cleanliness and care before dining—a quiet moment to prepare for the meal ahead.

Rainy-Day Umbrella Service

On rainy days in Japan, shops often provide plastic covers or lockers for umbrellas to keep floors clean and safe. Simply slip your umbrella into a sleeve or store it in a locker before entering — it’s a free act of omotenashi (hospitality).

These thoughtful touches prevent slippery floors and show Japan’s deep respect for cleanliness and consideration.

When leaving, dispose of the plastic cover in the provided bin—a small gesture that turns even rainy days into a pleasant experience in Japan.

Modesty and Humility

In Japan, modesty is deeply valued, and people often respond to praise with humble replies—a reflection of kenson (謙遜, humility).

Even in language, phrases like tsumaranai mono desu ga (“It’s just a small thing”) express respect rather than self-deprecation.

Quiet humility often speaks louder than confidence—a subtle strength that builds trust and harmony in Japanese culture.

Gift-Giving (Omiyage)

Giving small gifts or souvenirs, called omiyage (おみやげ), is a heartfelt way to show appreciation in Japan.

People often bring back local treats from trips or give seasonal gifts like ochugen (summer) and oseibo (year-end). Presentation is key—gifts are neatly wrapped and offered with both hands, then opened later to avoid awkwardness.

Even a small token from your home country shows gratitude and helps you connect through Japan’s thoughtful omiyage culture.

Public Manners and Etiquette

In Japan, public behavior is guided by the idea of not inconveniencing others (meiwaku wo kakenai, 迷惑をかけない).

People line up quietly, keep phones on silent, and speak softly—even crowded trains remain calm. Eating while walking is discouraged, trash is carried home, and smoking is limited to designated areas.

By following these quiet rules, visitors show respect and experience Japan’s culture of harmony and consideration firsthand.

Worship at Shrines and Temples

At Shinto shrines, visitors purify themselves at the temizuya (water basin), then bow twice, clap twice, make a wish, and bow once more.

At Buddhist temples, simply bow with hands together and light incense if offered. Move quietly, remove hats or sunglasses, and avoid walking in the center path.

By following these simple steps, you can respectfully take part in Japan’s timeless spiritual traditions.

New Year’s Traditions (Oshogatsu and Otoshidama)

New Year’s (Oshōgatsu) is Japan’s most important holiday, centered on family, reflection, and good fortune.

Before January 1st, families clean their homes (ōsōji) and decorate with kadomatsu or shimekazari to invite luck. On New Year’s Eve, people eat toshikoshi soba for longevity, while temples ring bells 108 times to cleanse desires.

On New Year’s Day, families enjoy Osechi Ryori and children receive otoshidama (money gifts). Peaceful, traditional, and full of gratitude, Japan’s New Year is a serene celebration of renewal.

Learn more about Japan’s annual events.

Coming-of-Age Ceremony (Seijin-shiki)

Every January, Japan celebrates Seijin-shiki, the Coming-of-Age Ceremony for those turning 20 — marking the start of adulthood.

Young men wear suits or hakama, while women don colorful furisode kimono. After a short ceremony at city halls, friends and families celebrate this new chapter together.

Seijin-shiki symbolizes responsibility, gratitude, and community— values that shape Japan’s journey from youth to adulthood.

Harmony with Nature and Symbols of Good Fortune

In Japan, nature and symbols of good fortune are deeply woven into daily life.

The four seasons are celebrated through food, art, and festivals — spring brings cherry blossoms, summer offers wind chimes and cool noodles, autumn glows with maple leaves, and winter welcomes yuzu baths and warm hot pots.

This love of nature reflects mono no aware — the beauty of impermanence.

Cranes symbolize longevity and hope, while Daruma dolls represent perseverance and luck. Folding 1,000 origami cranes (senbazuru) expresses prayers for healing, and painting a Daruma’s eyes reminds people to keep faith until their goals are fulfilled.

Rooted in Shinto beliefs and centuries of tradition, these customs reflect Japan’s quiet optimism and harmony with nature —a spirit of resilience and gratitude that continues to inspire today.

Cultural Background — Shikitari and Japanese Values

We’ve learned about many Japanese customs, or shikitari.

Now, let’s explore their background — what they mean, how they differ from everyday manners, and why respect and modesty are so central in Japan.

Understanding these deeper values helps you explain Japanese culture clearly and appreciate its harmony and thoughtfulness on a whole new level.

What Is “Shikitari”?

Shikitari (しきたり) refers to Japan’s traditional customs — unwritten rules passed down through generations that quietly shape daily life. These aren’t laws but cultural habits learned naturally from family and community.

For example, taking off shoes or saying itadakimasu are practiced without formal teaching. They reflect Japan’s deep values of respect, harmony, and cleanliness, appearing in everything from household routines to weddings and seasonal festivals.

Many shikitari evolved uniquely as Japan blended foreign influences into its own culture. For Japanese people, they’re second nature — but for visitors, understanding them reveals Japan’s “cultural DNA”, the gentle traditions that define everyday life.

The Difference Between Customs, Manners, and Etiquette

You might wonder how shikitari (customs) differ from general manners or etiquette.

In Japan, shikitari are unique traditions passed down through generations — like bowing or sending nengajo (New Year’s cards).

Manners, on the other hand, are universal acts of politeness, such as saying thank you or waiting your turn.

Simply put, shikitari are cultural, while manners are social.

Knowing both helps visitors show respect and move gracefully through Japanese society.

For more insight into how Japanese manners are viewed abroad.

Why Modesty and Respect Are Central in Japan

Modesty and respect lie at the heart of Japanese culture, shaped by Confucian harmony and Bushidō (武士道, bushidō) discipline.

Shinto’s reverence for nature and Buddhism’s teaching to release the ego further nurture humility.

In daily life, people often “read the air” (kuuki wo yomu, 空気を読む) to sense others’ feelings and avoid conflict. Politeness often means indirectness—saying “That might be difficult” instead of a direct “No.”

These customs sustain social balance and create the calm, respectful atmosphere that visitors so often admire in Japan.

How Religion and History Shape Everyday Customs

Many Japanese customs stem from Shinto (神道, shintō) and Buddhism, the spiritual foundations of Japan.

Shinto’s focus on purity explains rituals like removing shoes, washing before prayer, and valuing cleanliness.

Buddhism introduced respect for all life, inspiring traditions such as itadakimasu before meals and Obon, the festival honoring ancestors.

Over time, these beliefs blended into daily life — tea ceremonies, shrine visits, and even bowing carry spiritual meaning more than conscious religion.

Modern Japanese may not think of them as “religious,” yet they practice them naturally.

Understanding these roots reveals how Japan’s manners grew from centuries of faith and harmony that still guide everyday life.

Frequently Asked Questions About Japanese Customs and Manners

Even with a good grasp of customs, you might still have practical questions.

Let’s address some frequently asked questions (FAQs) that travelers and newcomers often have about Japanese manners and etiquette.

These short Q&As will help you handle common situations smoothly and clear up a few myths or worries about behaving politely in Japan.

Do Japanese people tip in restaurants?

Tipping is not practiced in Japan.

Excellent service is already included in the price, and leaving extra money can cause confusion — staff may even chase you thinking you forgot your change.

Instead, express gratitude with a warm arigatō gozaimashita and a smile.

At high-end inns or with private guides, a small gift may be offered, but it’s not expected.

Enjoy Japan’s omotenashi spirit of genuine hospitality — where good service is given freely, no tip required.

Can I talk on my phone on the train?

In Japan, talking on the phone in trains or buses is considered rude.

Keep your phone on silent — known as “manner mode” — and avoid calls. If a call is urgent, step off at the next stop or use the designated phone area on long-distance trains like the Shinkansen.

Texting or browsing quietly is fine, but always keep the sound off.

If your phone rings, silence it quickly and give a small nod of apology.

These simple habits show respect for others and help preserve Japan’s calm, peaceful travel atmosphere.

Should I take off my shoes in restaurants or temples?

In Japan, remove your shoes when you see a shoe rack, tatami mats, or a raised floor.

Homes, ryokan inns, and traditional restaurants have a genkan (entrance) for this, often with slippers provided.

At temples and shrines, shoes stay on outdoors but come off inside wooden or tatami halls.

When unsure, simply follow others.

This thoughtful custom keeps spaces clean and shows respect — a hallmark of Japan’s mindful indoor culture.

Explaining Japanese Culture to the World

Explaining Japanese culture is a rewarding way to connect people across borders.

Use the PREP method — Point, Reason, Example, Point — to clearly explain customs and their meaning.

For example:

“In Japan, people remove their shoes indoors to keep the home clean — it’s a sign of respect.”

Be empathetic, share personal stories, and describe differences as unique, not strange.

With clarity, warmth, and curiosity, you can inspire understanding and appreciation for Japan’s traditions — from bowing to tea ceremonies — and truly become a cultural bridge.

旅をこよなく愛するWebライター。アジアを中心に16の国にお邪魔しました(今後も更新予定)。

ワーホリを機にニュージーランドに数年滞在。帰国後は日本の魅力にとりつかれ、各地のホテルで勤務。

日本滞在が、より豊かで思い出深いものになるように、旅好きならではの視点で心を込めてお届けします!